My great-great grandfather, James P. Miller, was born August 22, 1828, in Crawford County, Georgia. As the son of planter William R. Miller, and his first wife, Elizabeth Sanders, James grew up in relative comfort and was attended to by slaves. As an adult, he worked for a time on his father’s plantation, but after his marriage to Mary A. Jameson in 1853, he acquired and ran a hotel in Talbotton, Georgia, county seat of Talbot County. He also owned a tavern, possibly connected to the hotel, and even owned 50% of a distillery. The product of that distillery, it can be assumed, was sold in the tavern. During the Civil War it appears that he also owned a wholesale business centered in a warehouse in Geneva, Georgia, eight miles south of Talbotton. Geneva is 30 miles east of Columbus, Georgia. This warehouse played a small part in the largest cavalry raid of the war, a campaign led by United States Army Brigadier General James Harrison Wilson. It is now known as Wilson’s raid.

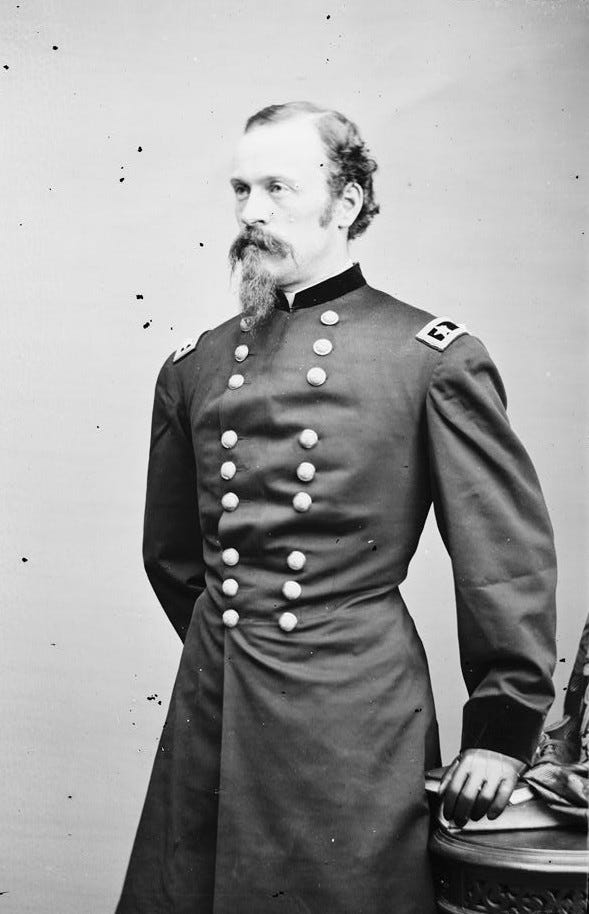

James Harrison Wilson was born in 1837 in Shawneetown, Illinois, a town on the banks of the Ohio River – and across from the slave state of Kentucky. His father, Harrison Wilson, was a Virginian who came to Illinois by way of Kentucky. He served as a volunteer rifleman in the War of 1812 with the rank of ensign and was a Justice of the Peace for Gallatin County, Illinois, hearing civil actions, and misdemeanor crimes. His mother, Catherine, was the second wife of Harrison Wilson.

James Harrison Wilson graduated sixth in his class from West Point in 1860 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant of engineers, but by May of 1863, at the age of 25, had attained the rank of Brigadier General and was a cavalryman. He remained a cavalryman for the duration of the war.

In his book Yankee Blitzkrieg: Wilson’s Raid Through Alabama and Georgia, Professor James Pickett Jones wrote that Wilson believed that cavalry had been misused throughout the war. Cavalry units were scattered throughout the infantry and were frequently used as guards for the supply train, messengers, and scouts. Wilson believed that massed cavalry could function as a highly mobile strike force that could be deployed wherever needed and once there, could fight dismounted. He wasn’t alone in his thinking. General Philip Sheridan shared his beliefs.

In 1865 cavalry raids were nothing new. During the Vicksburg campaign of late 1862, and early 1863, General Benjamin Grierson led a force of 700 cavalry into Mississippi. Moving fast and living off the land, his raiders confused Confederate commanders and disrupted lines of communication, but it was a mission of reconnaissance and diversion, and not an invasion.

Wilson himself led a raid south of Petersburg, Virginia in 1864. His cavalry force tore up 60 miles of Confederate railroad, and disrupted their transportation. Though the raid was considered a success, Wilson’s force suffered heavy losses, and lost all his wagons and artillery.

In October of 1864, Grant sent Wilson west to serve as General William Tecumseh Sherman’s head of cavalry, but when Sherman started his march to the sea, he sent Wilson and his cavalry to serve under the command of General George H. Thomas. Wilson and his cavalry contributed to the disastrous Confederate defeat at Nashville that ended all fighting in Tennessee.

Wilson was then ordered by General Thomas to establish his headquarters in Huntsville, Alabama. He instead, chose extreme northeastern Alabama on the north bank of the Tennessee River. The land was higher and drier, and thus, healthier.

The idea for Wilson’s raid originated with General Sherman who, when he was planning his march into Georgia, suggested a cavalry invasion of Alabama. Wilson wouldn’t let the idea die and wrote countless letters to headquarters in support of the idea. Once the Confederates were shattered at Nashville, the suggestion became a reality.

Wilson wrote in his diary: “In our next war our cavalry ought to play a proper part. I desire above all things to be instrumental in bringing this about.”

Ulysses S. Grant approved the raid, and envisioned a campaign limited to Alabama and involving about 5000 horsemen to disrupt lines of communication, lower Confederate morale, and support General Canby’s attack on Mobile. General Thomas thought about 10,000 men should go. Wilson wanted to take his entire force.

While Wilson lobbied to take his entire command, he was ordered to send 5000 men to General Canby. He dismounted an entire division because they didn’t have enough mounts. The mounts that they did have were sent out to the other divisions, and trying to procure more mounts became another project.

In the meantime, his men trained and worked on their riding skills, especially their jumping. Wilson was reputed to be an accomplished horseman, and he wanted his men to ride as well as those of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose forces he would be facing in Alabama.

Not that Forrest had many men to send against Wilson. They had retreated from Nashville in some disarray and Forrest had them spread out around Alabama and Mississippi. He had also furloughed many of his men with instructions to re-equip and procure mounts.

In the Union cavalry, the soldiers were supplied with their horses and equipment by the army. In the Confederate cavalry, soldiers had to supply their own horses and equipment.

Wilson never got all the horses he needed. General Canby’s needs were prioritized over his own. He was able, though, to equip his entire corps with the new Spencer seven shot repeating carbines.

The campaign was scheduled to start March 5th, but heavy rains and flooding of the Tennessee River led to a postponement until the rains stopped, and the water levels dropped. To make matters worse, on the 9th of March it snowed in the afternoon, and temperatures dropped below freezing overnight. Finally, on the 12th of March, the troops started the perilous crossing to the south bank of the river. All except 3500 cavalrymen who had no horses. Wilson briefly flirted with the idea of bringing them along, and gradually equipping them with captured mounts, but in the end, left them behind.

Another delay occurred when they had to wait for forage for the horses. Scouts had reported the first 80 miles of their route was barren. By the 21st of March, the forage had arrived, and orders were given. Reville sounded at 3 A.M. the next morning, and when dawn broke “Boots and Saddles” was sounded. The first of 13,480 cavalrymen mounted up, and started to ride south in ranks of two, followed by 250 wagons, 56 mules carrying pontoon bridges, artillery, and 1500 men on foot. The invasion of Alabama had begun.

After the crossing the troops separated. One division turned east and then south. The hope was the dispersal would confuse the Confederates as to their objective and force them to spread their already thin ranks out more. Their goal was not occupation, but to destroy infrastructure that supported the Confederate military, and tie up Confederate forces in support of Union operations in Mobile and Pensacola. Their first act of vandalism came when they burned a flour mill.

By the 28th of March it became apparent that their objective was the Selma, Alabama area, a Confederate iron and steel center. Before that, Wilson sent a force of 1500 men west to Tuscaloosa to destroy the military academy at the University of Alabama.

The vanguard of Wilson’s force encountered Confederate troops outside of the town of Montavello. The Union troops drove them away, and then occupied the town, home of a large iron works which was subsequently destroyed. As they left Montavello the Union forces fought a 14-mile running battle with the Confederates. Even the arrival of legendary Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest failed to stop them. By April 2nd they were approaching Sema, home to a large Confederate arsenal.

In Selma, Forrest tried to rally his weary troops, and even impressed civilian males into the defense of the city, arming them with whatever weapon happened to be at hand. The Union attack started on April 2nd. The Confederate defenses collapsed with the soldiers fleeing or laying down their arms and surrendering. By nightfall the city had been taken. Wilson’s men spent the next week destroying the arsenal and naval foundry. Wilson’s horse, Sheridan, was wounded in this battle. Yes, he named his horse after Phil Sheridan.

Coincidentally, April 2nd was the date Confederate president Jefferson Davis fled Richmond, Virginia.

Wilson’s force occupied Montgomery on April 12th, three days after Lee surrendered at Appomattox. He entered the city unopposed as the Confederate forces evacuated to Columbus, Georgia. The city’s civilian leadership surrendered the city. Wilson left General McCook as military commander of the city. During a flag raising ceremony McCook gave a speech attended by civilians and a paper described as “Union men of the 11th hour.”

It was at this point that Wilson’s orders gave him the freedom to do whatever he thought best. He could go south and support the assault on Mobile or turn east into Georgia. Wilson elected to go east to, as he wrote in his memoir, “breaking things’ along the main line of Confederate communications.” Columbus, Georgia was the next target.

To get there, he had to cross the Chattahoochee River. His engineers could construct a pontoon bridge across the river, but progress would be slow as the river was still high from heavy rains. He again divided his force. A small force under the command of Colonel Oscar LaGrange would attempt to take the bridge at West Point, Georgia intact. The bulk of the force under Wilson would do the same at Columbus.

On April 16th both Union forces attacked their respective targets 35 miles apart. West Point was a railroad center, but Columbus was a manufacturing center, especially in textiles, but rifles and revolvers were manufactured there. Upon Sherman’s approach, everything movable in the Atlanta arsenal had been moved to Columbus. It was also the headquarters of the Confederate quartermaster corps.

The Confederate forces defending Columbus were a mishmash of regular army, reserves, militia, and citizen volunteers. Even with all that they didn’t have enough men to man all the defensive works of the city, so the decision was made to concentrate their forces in defense of the bridges on the Alabama side of the Chattahoochee River in the town of Girard.

The first of Wilson’s force was spotted at about 2 P.M. on Sunday, April 16th by Confederate pickets who promptly fell back behind their lines. Wilson waited until his artillery arrived at the front, and then launched the attack at about 8 P.M. Confusion soon reigned supreme on the battlefield as Union forces sometimes literally stumbled about in the dark. Many of the Confederates were seeing their first action. Wave after wave of dismounted Union cavalry charged the Confederate defenses, and then fell back. It was then discovered that Union troops had somehow snuck past the Confederate lines in the darkness and were now holding the Alabama side of a bridge behind their lines. Union forces started crossing this bridge into the city, and Confederate resistance collapsed with forces surrendering or fleeing. By 11 P.M. the city of Columbus was taken.

On the 17th Wilson gave command of the city to General Edward Winslow of Iowa and ordered him to destroy anything that might be of use to the Confederates. The destruction of factories, storehouses, the arsenal, and naval facilities on the river began. By the evening, much of Columbus was a smoldering ruin.

Although Wilson didn’t know it at the time, he had fought his last battle, many consider the Battle of Columbus to be the last major battle of the war – east of the Mississippi. He and his remaining force rode on to Macon, Georgia. While enroute he found out that Lincoln had been assassinated on the April 15th, and that Johnston had surrendered the remaining Confederate forces to Sherman in North Carolina. The war was over. When he got to Macon on April 20th , he accepted the city’s surrender.

On May 10, 1865, Wilson’s cavalry captured Jefferson Davis in Irwin County, Georgia.

Wilson wrote 50 years later that had he known what had happened in Virginia – Lee’s surrender – he would not have inflicted as much damage on Columbus as he did.

The “boy general,” as his men called him, led his men on a 28-day, 525-mile-long raid. His force was comprised almost entirely of units from Iowa, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, Missouri, and Kentucky as well as U.S. Army cavalry. It was the largest cavalry action of the war, and the most successful. His actions at Montgomery, Selma, and Columbus – cities that had been largely untouched by the war – extinguished what hope the Confederacy had of reassembling, rearming their forces, and carrying on the fight. The capture of Jefferson Davis in South Georgia indicated he may have been trying to get to Alabama or Texas for that same purpose. The raid’s goals were met.

Wilson left the army in 1870 and worked as a railroad construction engineer. He came back to the army in 1898 for the Spanish-American War, and the 1901 Boxer Rebellion, after which he retired for good. He died in 1925 in Wilmington, Delaware.

Thirty miles east of Columbus on a railroad line lies the small town of Geneva, Georgia. In 1865 my great-great grandfather had a warehouse here. Next week in Part II I’ll write about what happened when Wilson’s Raiders, on their way to Macon, passed through Geneva.

The major sources for this article were Yankee Blitzkrieg: Wilson’s Raid Through Alabama and Georgia by the late James Pickett Jones. The edition I used was originally published in 1987 by the University of Georgia Press.

I also used – in true 19th century style – a tome titled Columbus Geo., From It’s Selection as a “Trading Town” in 1827 To Its Partial Destruction by Wilson’s Raid in 1865. It was compiled by John H. Martin, and was published by Thos. Gilbert, Book Printer and Binder in Columbus, Georgia in 1874. I found it at Archive.org.

Also used was Ancestry.com.